Managing Life after the Finish Line (Damien Smith Autocar)

What next for racing drivers when the chequered flag falls on their careers?

Damien Smith meets one who’s making the most of what he knows best. When to quit and what to do with rest of your life: those are the two the biggest, most daunting questions for any professional sportsperson.

You’ve dedicated yourself from childhood to the pursuit of excellence, you’re still relatively young, perhaps only half-way through your lifespan – and you still love what you do. But what now? “It’s a bigger deal than most people outside of professional sport realise,” says Johnny Mowlem, who spent 20 years being paid to race sportscars around the world, then finally called time on his professional career in 2017. “I found it tough. I was fortunate to reach the level of racing internationally but it involved so much travel that for the last five or six years I was thinking about an exit strategy, while not really doing a lot about it.

“In my last year and a bit I noticed I was probably clinging on tighter in terms of my performances. I was still delivering on track, for example even in my last season I was fortunate enough to get the overall prototype challenge pole position at the Daytona 24 Hours in the wet, but I could sense deep inside I was having to dig deeper to get to a level that had felt relatively effortless before.” Mowlem always has been a bright chap. Unlike most of his racing driver breed, he went to university and gained a degree in Spanish and economics, before dedicating himself to racing. Promising in Formula 3, he only fell off the single-seater ladder because of money, then reinvented himself as a GT driver. Winning a remarkable 17 races out of 17 in the 1997 UK Porsche Carrera Cup put him on the map, launching him into a career than earned him 10 starts and a class podium at the Le Mans 24 Hours, other overall podiums and class victories at Daytona and Sebring and a European Le Mans Series GT title.

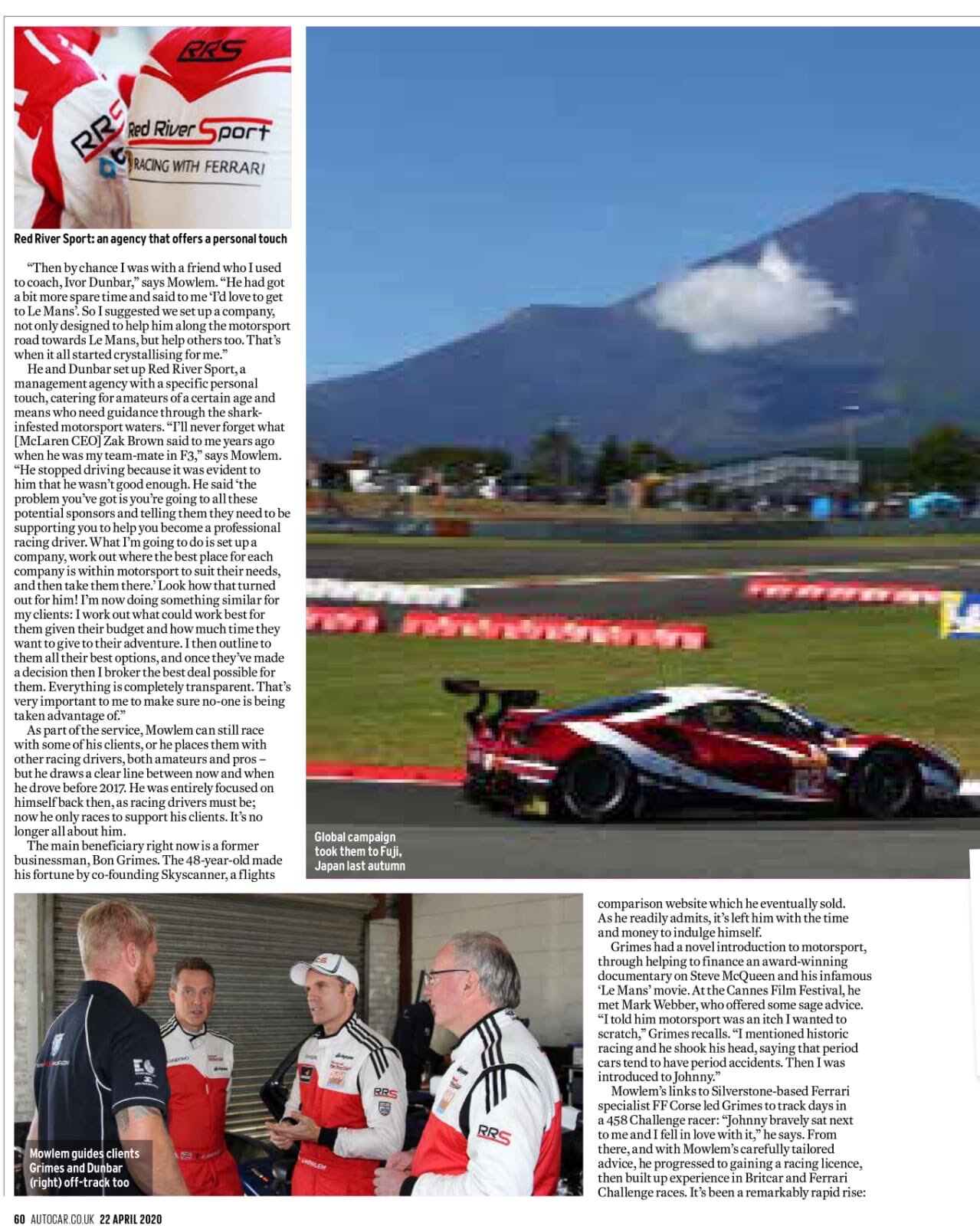

Red River Sport: an agency that offers a personal touch “Then by chance I was with a friend who I used to coach, Ivor Dunbar,” says Mowlem. “He had got a bit more spare time and said to me ‘I’d love to get to Le Mans’. So I suggested we set up a company, not only designed to help him along the motorsport road towards Le Mans, but help others too. That’s when it all started crystallising for me.” He and Dunbar set up Red River Sport, a management agency with a specific personal touch, catering for amateurs of a certain age and means who need guidance through the shark-infested motorsport waters. “I’ll never forget what [McLaren CEO] Zak Brown said to me years ago when he was my team-mate in F3,” says Mowlem. “He stopped driving because it was evident to him that he wasn’t good enough.

He said ‘the problem you’ve got is you’re going to all these potential sponsors and telling them they need to be supporting you to help you become a professional racing driver. What I’m going to do is set up a company, work out where the best place for each company is within motorsport to suit their needs, and then take them there.’ Look how that turned out for him! I’m now doing something similar for my clients: I work out what could work best for them given their budget and how much time they want to give to their adventure. I then outline to them all their best options, and once they’ve made a decision then I broker the best deal possible for them. Everything is completely transparent.

That’s very important to me to make sure no-one is being taken advantage of.” As part of the service, Mowlem can still race with some of his clients, or he places them with other racing drivers, both amateurs and pros – but he draws a clear line between now and when he drove before 2017. He was entirely focused on himself back then, as racing drivers must be; now he only races to support his clients. It’s no longer all about him. The main beneficiary right now is a former businessman, Bon Grimes. The 48-year-old made his fortune by co-founding Skyscanner, a flights comparison website which he eventually sold.

As he readily admits, it’s left him with the time and money to indulge himself. Grimes had a novel introduction to motorsport, through helping to finance an award-winning documentary on Steve McQueen and his infamous ‘Le Mans’ movie. At the Cannes Film Festival, he met Mark Webber, who offered some sage advice. “I told him motorsport was an itch I wanted to scratch,” Grimes recalls. “I mentioned historic racing and he shook his head, saying that period cars tend to have period accidents. Then I was introduced to Johnny.” Mowlem’s links to Silverstone-based Ferrari specialist FF Corse led Grimes to track days in a 458 Challenge racer: “Johnny bravely sat next to me and I fell in love with it,” he says.

From there, and with Mowlem’s carefully tailored advice, he progressed to gaining a racing licence, then built up experience in Britcar and Ferrari Challenge races. It’s been a remarkably rapid rise: programmes in an LMP3 prototype and GT3 in the Asian Le Mans Series followed – and now he finds himself racing around the globe in a potent Ferrari 488 GTE, with Mowlem as his co-driver in the ‘Am’ class of the World Endurance Championship. That first track day at Brands Hatch was in 2015. From that standing start, less than five years later he’s preparing for his first Le Mans 24 Hours. Too much, too soon? Absolutely not, insists Mowlem. “Priority number one is keeping Bon safe,” he says. “Priority number two is having fun. Third is doing well – although he might not always agree with that order. Bon’s commitment and dedication is quite astonishing, but that’s the kind of guy he is. He obviously has a good amount of natural ability but it’s how he has dedicated himself to improving that impresses me.”

Being in the WEC pushes you to get better quicker.

Grimes admits Le Mans was not originally the intention, but is grateful how fast things have progressed with Mowlem’s guidance. “Doing the WEC shows how much you’ve got to learn, and not just about the car,” he says. “One of the challenges I’ve had was when I started I ran in the faster classes. Now I have LMP1s coming up behind me and I’ve had to learn to deal with being ‘traffic’. It’s also one of the biggest GTE Am fields the WEC has ever had. And I’m the only one not to have done a season before. But being in that environment pushes you to get better quicker. Each round we learn lessons and we’ve made. mistakes. But my one-lap pace is now very good. I just need to work on my concentration and consistency for race pace.”

As co-driver to Grimes, Mowlem will notch up another Le Mans start too, but he insists that’s not important. “Eventually I am going to step back and rather than be a player-manager I’ll just be the manager,” he says. “My days of getting paid by a team to race are done. I still love driving race cars, but my priority is to put my clients first and give them the best possible opportunities both on and off the track.” But from staring into the abyss of life after racing, Mowlem is now staring up at the stars with a clever business that makes sense, both to him and his wealthy clients. Not all will want to aim for Le Mans, as Johnny point outs. But whatever level they race at, they know their coach will always be there to save them from the shark bites.

More Talent on the Books

Coaching amateurs as the face of Red River Sport is Johnny Mowlem’s focus, but he’s already diversified to help others further up the motor racing chain. Among them is former Audi LMP1 ace and multiple Le Mans podium finisher, Oliver Jarvis. The 36-year-old is racing for Mazda in the US (below) and Bentley in Europe this year. He’s already had a long, varied and successful career, so at this stage why does he need Johnny? “I’d always looked after myself,”

Jarvis says. “Things were very simple at Audi. Contracts were standardised and there wasn’t much to be discussed. But when Audi pulled out of LMP1 [in 2016] I realised I had been living in a bubble. I needed help, someone to bounce ideas off and to act as a buffer. I’ve always been slightly ‘anti-manager’ because 90% aren’t very good. There are a lot who latch on and want money for very little.

But Johnny has been great for me. I’ve developed so much as a person since Audi pulled out.

I could do a lot of it myself, but I like having Johnny there. It takes the pressure off. I can focus on the racing itself and not get distracted.” He can also watch his manager and take note for the day when the racing stops for him, too.

As featured in Autocar magazine / 29th April 2020